Monster: The Ed Gein Story

By Maureen McCabe

Monster: The Ed Gein Story is a chilling exploration of the life and crimes of the Wisconsin serial killer and grave robber dubbed the “Butcher of Plainfield. Gein’s gruesome legacy served as the inspiration behind such horror classics as Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and The Silence of the Lambs, and is believed to have influenced real-life serial killers like Ed Kemper and Richard Speck. Created by Ian Brennan, and produced by Ryan Murphy, it is the third installment of the Monster series, following the successes of The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (2022) and The Lyle and Erik Menedez Story (2024), and like them it blends biographical facts with psychological insights and sensational embellishments into a gripping, but also deeply disturbing, narrative.

Born in 1906, Gein was the child of an alcoholic father and an abusive, religious fanatic mother. He grows up to be a seemingly gentle, awkward man who is treated with varying degrees of pitying patience by the townspeople and neighbors he interacts with. After the unusual death of his brother, which was never solved, (but the series strongly hints was Gein’s doing), and then of his mother by a stroke, Gein becomes increasingly isolated and unbalanced. Inspired by the comic books and newspaper articles his beautiful, macabre friend Adeline Watkins shares with him which detail Nazi atrocities, he begins digging up female corpses and mutilating their bodies to create trophies such as bowls and lampshades. He is questioned in relation to the suspicious circumstances regarding his brother’s death, and also the death of tavern owner Mary Hogan, but manages to evade detection until 1957. Searching for clues in the disappearance of Bernice Worden, the owner of the town’s hardware store, the authorities search his property and find Worden’s body in the barn, “trussed up like a deer,” and his house full of mutilated body parts. Deemed insane and unfit to stand trial, Gein would spend the rest of his life in a mental institution.

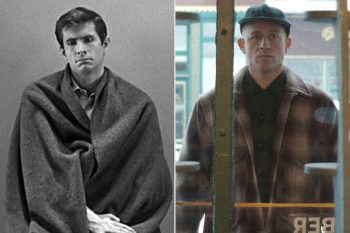

The production values in the series are first-rate especially the cinematography, which is strikingly beautiful, with gorgeously grim shots of the stark Wisconsin landscape. The dark interior shots of the Geins’ rugged barn and home form a chiaroscuro of the horrific and the mundane. Likewise, the soundtrack is equal parts beauty and nerve-wrecking adrenaline. The acting is compelling and fearless. Charlie Hunnam is excellent as Gein, giving him a shambling walk and an affected high—pitched voice. His aspect of bullied meekness helps explain why, when he is questioned in regards to the murder of Hogan, the witness who states he saw Gein’s truck outside her tavern, in the next breath tells the sheriff that it couldn’t have been Ed, “he wouldn’t hurt a fly.” Especially in the later episodes, where the show works hard to build up sympathy for him, Hunnam is affecting as the aging, and still tortured, Gein. Laurie Metcalf’s portrayal of his dominating, puritanical mother is truly the stuff of nightmares, as is Suzanna Son’s Adeline, the beautiful girl next door with a heart of darkness. Vicky Krieps as the notorious Nazi “Beast of Buchenwald” Ilse Koch whose horrific deeds supposedly inspired Gein, and Joey Pollari as Tony Perkins turned in haunting performances.

But the series, at eight episodes, is much too long and the pacing overall is slow but jerky. Some of the episodes seem unnecessarily padded out, while in others major events are covered in a flash. It doesn’t help that in order to emphasize Gein’s tenuous hold on reality, flashbacks, jump cuts, and montages are employed throughout to show several events in explicit detail that are then cast into doubt or shown not to have happened. This approach gives the show a hallucinatory quality that works well thematically, but makes it difficult for the viewer to tell what’s reality and what’s Gein’s tortured imaginings. Worse, some of the dramatizations seem included purely for shock value. There is enough gruesomeness without including Ted Bundy, who is seen murdering two teenage girls. Later Gein is shown helping in the identification and capture of Bundy, which never happened.

Perhaps the most unsettling thing about the series is that, as in the previous installment in the Monster series, The Ed Gein Story obsesses over that essential question: “Are monsters born or made?” The Menedez brothers were shown to be victims of sexual abuse and trauma to explain their actions. Similarly, here Gein is shown to be a product of a severely dysfunctional family unit and suffering from undiagnosed mental illness for most of his life. These series suggest that the answer to the question consuming the creators of Monster has to be “both.” But in The Ed Gein Story we don’t have to try and guess what they believe. Tom Hollander as Alfred Hitchcock lays it out for us plainly. Hitchcock, staring into the camera, and thus directly at the audience, declares that “monsters are made. By us.” If that’s true, if reading about barbarism like Ed Gein did can push someone over the edge into madness, if the appetite for sensationalized true crimes not only helps popularize but also gives rise to other vicious criminals, then the moral seems clear: “be careful what you look at.” It’s an ironic and, some may say, hypocritical take for a series that delights in being so intensely graphic.

Maureen McCabe

Maureen McCabe is a native Southern Californian who enjoys mysteries and thrillers, despite being easily scared.