“STANLEY KUBRICK’S “THE SHINING””:

COMPREHENSIVE NEW TASCHEN PUBLICATION IS THE FINAL WORD ON THE HORROR CLASSIC

review by Tom Lavagnino

Mountain climbers have Everest. Race-car drivers the Indy 500. Deep-sea explorers the Mariana Trench.

And now fans of Stanley Kubrick’s horror classic THE SHINING have a holy grail of their own — thanks to the late J.W. Rinzler, award-winning Pixar animator Lee Unkrich, and their combined authorial effort: the massive mega-box “STANLEY KUBRICK’S ‘THE SHINING.’”

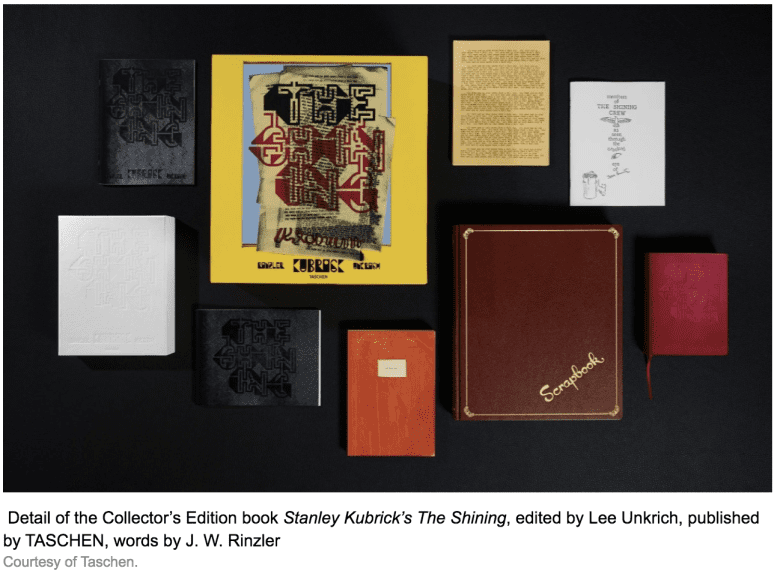

The just-published Taschen creation is the last word in SHINING scholarship, documentation, and detail-oriented trivia; its near-overwhelming 2,200 plus pages of photographs, sketches, interviews, and annotated shooting script (not to mention a ream of paper re-creating “ALL WORK AND NO PLAY MAKE JACK A DULL BOY” pages, to chilling effect) comprise a veritable everything everywhere all at once of THE SHINING. If you’re the sort of super-fan who wants to see photos of young Danny Lloyd’s “sixth birthday” card from the set (signed by Kubrick, Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, et al), yeah, this is the publication for you.

Unkrich’s obsession with Kubrick’s classic began with his first viewing of the film at age 12. As his career at Pixar blossomed (he edited the original TOY STORY and co-directed both FINDING NEMO and MONSTERS, INC.), dedication to the SHINING project gradually consumed his life; he ultimately departed Pixar in 2019 (his final project was the Oscar-winning COCO), teaming with Rinzler on the finalizing of this stunning publication.

The authors deliver voluminous intel on THE SHINING, but also cheeky wit; the publication’s centerpiece is a meticulous 900+ page diary/compendium of the movie’s prepping, casting, shooting, post-production, and enduring legacy — presented in the form of a Gideon-esque “bible” (complete with ultra-thin pages and ribboned bookmark).

Are you a ScareTube fan who embraces the hypnotic allure of Kubrick’s classic? If so, read on. If not, stop reading here. (Die-hard fans will no doubt luxuriate in the following trivia-that-I-found-fascinating in the Rinzler/Unkrich creation — others beware!)

Before SK and co-scenarist Diane Johnson had even finished writing the screenplay for THE SHINING, an outline dated August 1, 1977 indicated that the finished film would run 145 minutes and 20 seconds. (As it happens, the original release of THE SHINING ran 146 minutes (prior to the post-release cutting of the “hospital coda” scene, which brought the “final version” run time down to 144 minutes.)

Despite SK’s strong relationship with the Warner Bros. brass (Ted Ashley / Frank Wells / and especially John Calley), tensions and conflicts concerning THE SHINING budget initially caused Kubrick to consider alternative financing (which SK goadingly referred to, in internal WB memos, as “AF”). But Kubrick was in an all-powerful negotiating position; he had the commitment from Jack Nicholson to star, very early on (October, 1977). (Given that Nicholson had won the Oscar 18 months earlier, and was one of the most bankable actors in the world, SK knew he had Warner Bros. wrapped around his finger.)

Kubrick also recognized that casting the role of six-year-old “Danny” was pivotal. Actor Leon Vitali was contracted, very early on, to work on THE SHINING — two years after he appeared, as an actor, in BARRY LYNDON. Kubrick observed that Vitali was instrumental, during the making of that film, in getting a great performance out of youthful co-star David Morley (playing the role of “Bryan Patrick Lyndon”); SK figured that, because he’d worked so well with Morley, he’d do the same with young Danny Lloyd. (Vitali’s success in doing so led to life-long employment with Kubrick, as we all know.)

Speaking of Danny Lloyd: Concern about union-mandated “U.K. work limitations for child actors” impacted the production on a continual basis. Consequently, Kubrick seriously considered shooting the entirety of THE SHINING in NYC, Long Island, or New Jersey. Officials in NJ even discussed “changing” the “child work hour requirements” to make the location more attractive to SK/Warner Bros.

Up until late in pre-production, Kubrick wanted either Slim Pickens (calling DR. STRANGELOVE!) or Ben Vereen to star as Halloran in the movie. But Nicholson’s friendship with Scatman Crothers (their bond was based on marijuana and golf!) ruled the roost.

Insurance issues also nearly derailed THE SHINING before shooting commenced. SK had experienced numerous on-set accidents on his prior films — necessitating high-end insurance claims. But the resulting delays in shooting those movies was a cause-and-effect dynamic that (it’s suggested) Kubrick actually kind of liked — because it gave him and his team more time and freedom to focus on other aspects of the production. (Indeed, after shooting for 28 days, Jack Nicholson injured himself when returning, after a party, to his rented flat in London at 104A Cheyne Walk. Without his house keys, he jumped the fence of the property — and landed badly. Production shut down for a month while Nicholson recovered, with the idle crew on “half pay” for the duration.)

Before shooting began, Steven Spielberg (doing preliminary prepping for RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK at an adjacent sound stage at Elstree Studios) stopped by the set to see Kubrick, who was one of his all-time idols. It was the first time they had ever met. “My heart started to race, my mouth was dry as I walked in, expecting to see a hundred people (on the set),” Spielberg said. “(But the stage) was empty except for The Overlook, which was overwhelming. The stage lights were on, so there was enough light to see the detailing of that amazing, amazing, Navajo-influenced set design. Stanley, in kind of a long, Columbo-style trench coat and full beard, was standing in the center of the set with a small cardboard model of the same set. He was hunched over the model with a Nikon camera and an inverted periscope lens taking still photographs of his cardboard facsimile. So I got introduced to Stanley, and Stanley put down his camera and greeted me warmly. I had a lifetime’s worth of questions ready to pepper him with, but he didn’t let me get a word in edgewise. Instead, he asked me a ton of questions about JAWS. I was able to ask one question before he had to go back to work. I said, “you have a dressed set here. It looks like it’s all ready to shoot. Everything’s here. Why are you using a cardboard model with the little cardboard figures?” He replied, “well, look how big the set is, Steven. This saves a lot of footwork.”

The enormous sets at Elstree remain, historically, some of the largest ever built for a U.K.-based movie; virtually all “remained in place” throughout the lengthy shoot (Kubrick wanted to have them available, at all times, in case he wanted to go back and re-shoot a sequence or two).

The climactic “hedge maze” (a radical departure from the original Stephen King novel, of course), was fashioned on the Elstree back lot by production designer Roy Walker for maximum realism. “Stanley challenged (us) that the maze was too easy (to extricate one’s self from),” notes Walker. “So we put him in there one Saturday morning, and he couldn’t find his way out.”

Kubrick had not met Jack Nicholson face-to-face until mere weeks prior to the start of the shoot — when Jack visited Stanley on the set during its final tweakings. As they greeted each other, Nicholson reached into his pocket and handed Kubrick several hundred dollars — explaining that his next-door neighbor, Marlon Brando, “owed Stanley the money” from “the poker game” they were playing during prep for ONE-EYED JACKS (the movie that Kubrick was all set to direct, 19 years earlier, but (infamously) walked out on — leaving Brando to direct it himself).

As production of THE SHINING began (and almost immediately fell behind schedule), there was a concerted effort, on the part of executive producer / Kubrick brother-in-law Jan Harlan, to arrange to shoot the “final two weeks” of the production in Amsterdam (due to those pesky U.K. union-mandated limits on Danny Lloyd’s time). Calculations were made to “construct the necessary sets” in the Netherlands for two weeks of filming. (This plan was never actuated.)

Kubrick kept his crew small (generally 16 to 18 technicians on-set), and forced them to multi-task (sometimes in theoretical violation of union rules); he quoted Napoleon, saying “I expect my generals to be able to lead a Calvary charge one day and boil a chicken the next.”

The pivotal early conversation scene, in the kitchen between Scatman Crothers & Danny Lloyd, which runs 4:55, took four full days to shoot (and a total of 225 takes from various camera set-ups). Although Kubrick was irritated by Crothers (complaining “he doesn’t know his lines!” when shooting the earlier scene when Crothers chronicles the vast holdings of the kitchen walk-in), there were no significant flubs, on any of the takes, in this Crothers-Lloyd scene — Kubrick simply wanted to push Crothers to the limit, on the one hand, and nail down the precise rhythms and measures of the dialogue (to a granular degree) on the other.

Kubrick’s meticulousness with Nicholson likewise caused friction. “There were 18 marks under the table that I had to follow when shifting position (in the sequence where Jack is crying at his writing desk and falls to the floor),” Nicholson said. “That would’ve driven some actors crazy, but I liked it. It was a challenge, like experimenting with a large number of interpretations for a part.” That was what Nicholson told the press. To Tim Bourne, his personal chef, Nicholson said, “(Kubrick) is crazy.” “The time Jack had to fall down,” Bourne recalls, “he came back and he was laughing about it and how insane this guy was, how there were light cues on the floor, pinpoints of light, where Jack’s fingers would have to land when he fell.”

After a shoot day was completed, and to ensure the safety of the negative, production footage was driven from the set to the (London) lab following a strict protocol using three cars: one in front as protection, the car with undeveloped film in the middle, and one following (in case there was a crash!).

Kubrick was continually changing the script, throughout the shoot, often mere minutes before sequences were scheduled to be filmed. “I was there the day Stanley’s mother (visiting from the USA) asked if she could come down to the set,” WB executive Julian Senior noted. “It was such a wonderful day because Stanley was clearly not that comfortable with having somebody else on the set, let alone your mother. She was holding the script, paging through it, and she said, ‘Stanley, it’s very interesting. Why are there so many different-colored pages?’ Stanley said, ‘Every time we make a script change, we tend to put it in a different color, so it’s immediately apparent.’ She nodded her head sagely, and she said, as such a lovely Jewish mother, ‘You certainly are making a lot of changes, Stanley.’ I thought, That’s it. There’s (Kubrick’s) career, summed up.”

Halloran, in the film, receives his “shining communique” from Danny whilst lying in bed. But Kubrick seriously considered having this moment occur “at a massage parlor” or “on a tennis court” (and even had the production suss out “American-style tennis courts in the U.K. that might suffice” for this (ultimately never-used) purpose).

After wrapping one evening, Kubrick drove himself home as usual (sometimes he would drive his daughter Vivian). “The police stopped him once,” assistant editor Gill Smith reports, “because he was driving slowly, quite late at night, and he had a gold Mercedes, quite conspicuous. When they looked in the car, he had a (SHINING prop) axe and a roll of cable and rope. He explained that he thought he might get snowed in or he might need to dig himself out, but they were very suspicious. They were ready to arrest him.”

The ending of THE SHINING originally concluded with the now-legendary “lost hospital scene” coda. “Stanley took the hospital scene out quite early on,” according to assistant editor Gordon Stainforth, “(but) Vivian Kubrick, who was extremely influential, was very strongly in favor of it, and persuaded Stanley that the film really needed the hospital scene. So it went back in.” (The scene was removed, after the movie’s first day in theaters, and the footage from each and every print sent directly to Kubrick in the U.K. — where it was disposed of. This footage no longer exists in any form.)

For the four European markets, Kubrick filmed new versions of the “ALL WORK AND NO PLAY MAKES JACK A DULL BOY” pages. Rather than merely translating the text, SK chose phrases familiar to audiences in those particular markets: For Germany, “NEVER PUT OFF TILL TOMORROW WHAT MAY BE DONE TODAY”; for Spain, “NO MATTER HOW EARLY YOU GET UP, YOU CAN’T MAKE THE SUN RISE ANY SOONER”; for France, “A BIRD IN THE HAND IS WORTH TWO IN THE BUSH”; for Italy, “THE EARLY BIRD CATCHES THE WORM.” Leon Vitali notes, “This was done by Stanley because he felt that to have a subtitle when it was screening in those four territories would jolt the viewer out of the (moment).” (Likewise, the various time/date titles, throughout the film, were also translated-and-inserted into foreign release prints.)

In 1982, two years after THE SHINING’s release, Ridley Scott was in post-production on BLADE RUNNER when Warner Bros. demanded a “coda” to the movie, to run over Harrison Ford’s (also studio-mandated) narration. Scott contacted Kubrick, to see if he could use some of the unused helicopter footage from the opening title sequence of THE SHINING, and SK gladly agreed to provide it. (The footage was modified, optically, from 1.85:1 to Cinemascope 2.35:1, thusly cutting out the Volkswagen from the bottom of the frame, replacing it with actors Harrison Ford and Sean Young, and putting them in the futuristic hover-sedan or “spinner.”) Producer Bud Yorkin sent Kubrick a letter, stating: “I can’t tell you how grateful both Ridley and myself are for your kindness in bailing us out of trouble.”

In the aftermath of THE SHINING’s release, Kubrick met again with Spielberg. “When Stanley was asking me all about what I liked and didn’t like about his movie, one of the things I said was, ‘There’s the scene where Shelley Duvall finds the book he’s been writing, and she goes through the pages,’” said Spielberg. “There was such an opportunity at that low angle, looking up at Shelley’s face, where you could’ve had the audience screaming and throwing their popcorn into the air if Jack’s face had simply grown out of her left shoulder and loomed. But, instead, you cut to a subjective point-of-view in which Jack comes out from behind one of the columns; there’s no real shock, no real jump.’ Stanley said, ‘The reason I didn’t do it your way is that’s exactly what the audience would have been expecting.’ I loved that answer.”

Stanley’s ultimate attitude about THE SHINING was: “You know, in a way, every scene (in this movie) has already been done in film. Our job is simply to do them a little better.”

Tom Lavagnino is a playwright, television producer and golfer (18 handicap) living in Southern California. www.tomlavagnino.com