Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders

By Maureen McCabe

Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders is the latest offering in the Cold Case series, a three-part documentary directed by Yotam Guendelman and Ari Pines and produced by Joe Berlinger, currently streaming on Netflix . The series does an excellent job recreating the horror and helplessness felt by residents of Chicago and most of the rest of the country when seven people died from ingesting extra-strength Tylenol capsules filled with cyanide in September of 1982. For people who don’t remember those days, it provides a brisk summary of the terrible events and how shocked and terrified people felt at the thought of such a trusted product, a pain reliever, becoming a murder weapon. Even for those of us who were around then, it gives a useful flashback to how things were then. So many things that we take for granted now, like tamper- resistant packaging for drugs, weren’t around then. Neither was social media: when the authorities wanted to warn the public of the danger of taking Tylenol and recall bottles from purchasers, they had the cops drive through the streets with loudspeakers broadcasting the information and volunteers go knocking door to door.

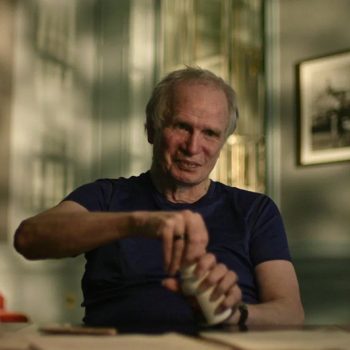

The Tylenol Murders is at its best in such evocative scenes and during its thoughtful, empathetic interviews with the families and friends of the victims, whose pain is still raw forty years later. Adding to their suffering is the fact that the case has never been resolved. Back then law enforcement focused on primarily on two suspects: a dock worker and amateur chemist named Roger Arnold, who was ruled out relatively quickly, and James Lewis, who penned an extortion letter demanding one million dollars be sent to a specific bank account in order for him to stop the killings. Lewis, who died in 2023, has always maintained that he wrote the letter in retaliation against his wife’s former employer, whose last paycheck to her bounced. The bank account listed in the letter was linked to her employer’s company. Among the most riveting scenes of the series are clips from the long interview the producers scored with Lewis, a man who went by several names, was accused but not convicted of several other crimes, including murder and rape, and certainly comes off as creepy enough to have perpetrated the poisonings. In one shudder-provoking scene, as he opens the inner seal on bottle of Tylenol with his nails, Lewis intones in his robotic voice, “Everybody who tries to open these bottles swears my name.” Lewis served ten years in jail for writing the extortion letter but law enforcement could never definitely place him in Chicago at the time of the murders (the postmark on the letter was from New York). Nor was DNA evidence ever found linking him to the contaminated bottles, despite more recent testing. The FBI maintains the case is still open and still ongoing, although most of the investigators from both then and now remain convinced that Lewis was the murderer.

Recently, though, as one of the victims’ daughter details, a new theory has emerged. Widespread distrust of drug manufacturers is another thing that didn’t exist in the eighties, but is ubiquitous now. At the time Johnson & Johnson, who manufacture Tylenol, were quickly ruled out as having any culpability for the deaths. They were lauded for their handling of the tragedy, and in fact their CEO was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan for demonstrating “the highest ideals of corporate responsibility.” Johnson & Johnson always maintained that the capsules had to have been tampered with after they left their plants and that cyanide was not present at any of their facilities. This turned out to be untrue, and the fact that the millions of bottles of Tylenol that were recalled to see if any others contained cyanide were tested by Johnson & Johnson themselves is shocking now. The recalled bottles were later destroyed by a company Johnson & Johnson hired, thereby eliminating the possibility of any later testing on them. Critics point out that of course Johnson & Johnson had a vested interest in absolving themselves; Tylenol was and still is a huge source of profit for them. But like so many things related to the murders, there is no definitive proof of this theory. The poisoned bottles came from two different plants, in two different parts of the country; for them to have tampered with in the same way seems logistically unlikely but not impossible.

The Tylenol murders may never be solved, but the victims’ families remain hopeful that one day they might get closure. While it is probably of cold comfort to those mourning lost loved ones, their deaths led to increased product safety that no doubt saved many lives in the decades since. The series does a fine job laying out the facts and theories and aftereffects of the case, which have been somewhat dulled by the passage of time, and is well worth being checked out.