by Maureen McCabe

The most horrifying true crime documentary of the last few years has no guns, no knives, no blood, and a body count in the hundreds of thousands. It’s Alex Gibney’s The Crime of the Century, a two- part, four- hour shattering examination of the opioid crisis that is destroying America that should be mandatory viewing for anyone interested in health care, public policy or the nature and science of addiction. In the opening few minutes, the documentary makes clear that this “crisis” did not arise from any unforeseen natural disaster but is in fact the inevitable consequence of a carefully organized crime. It then traces the development of the tragedy that has taken an estimated 500,000 lives in the last twenty years as it was orchestrated by Big Pharma and abetted by complicit doctors, defanged regulatory agencies, and politicians who allow drug and distribution companies to dictate policy in exchange for massive contributions. Exhaustively researched and featuring never- before- seen depositions and secret documents, it’s a searing indictment of overwhelming corporate greed and undeniable government malfeasance.

The first part focuses on the rise of Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family, who made billions from their aggressive marketing of OxyContin, a highly addictive drug that is much more powerful than morphine. Purdue covered their oyxcontin pills in a sealant that was supposed to allow them to enter the blood stream slowly, in a controlled release that the company claimed, without a shred of proof, would greatly reduce the “abuse liability.” Originally marketed for cancer and end- of- life patients in intractable pain, Purdue and its officials worked closely with the FDA to obtain approval to market it to the widest possible group of patients, basically anyone dealing with pain. The package insert included with each prescription, which was written largely by Purdue, falsely allayed doctor’s fears about addiction. Doctors were encouraged to prescribe staggering amounts of the drug. One patient shown on the documentary was taking up to fifty pills a day, the equivalent of two hundred hits of heroine, which Purdue insisted was safe and non-addictive. When patients began overdosing and then dying, and frightened sales reps and nurses began sounding the alarm, Purdue doubled down by inventing the theory of “pseudo-addiction,” which falsely claimed the people who seemed to becoming addicts were in fact patients in unresolved pain; the solution was to give ever increasing amounts of opioids to people already in the clutches of addiction. In the face of ever-increasing evidence of the addictiveness of their products, Purdue knowingly marketed stronger doses of oxycontin and continued raking in unheard of profits, thereby fueling the opioid crisis and laying the ground work for other companies to join in.

The second part switches to focus on rise of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid even stronger than oxycontin, an estimated hundred times more powerful than morphine. Relentlessly pushed by “entrepreneur” Dr. John Kapoor, who marketed it as a sublingual spray, Insys employed slick salespeople who enticed doctors to write more and more prescriptions for the highest doses by hiring them as paid speakers. But bribing doctors by compensating them well for brief speaking engagements wasn’t the only corrupt behavior the company engaged in. Insys trained a methodical sales force to get balking health insurance plans to pay for the extremely expensive product, which was labelled for end of life and breakthrough cancer pain, by engaging in deceptive tactics laid out in bullet point emails, giving out confidential medical information gleaned unethically from patient’s doctors and outright lying to the health insurers. There is some satisfaction in seeing Kapoor and employees face a rare reckoning. As the documentary makes clear, most of the major players in the opioid catastrophe have gotten off far too lightly. The Sacklers squirrelled away billions before Purdue filed for bankruptcy and the massive- sounding fines that were levied on them were in fact just a small fraction of their profits which, due to bankruptcy, might never be paid anyway. No one from the Sackler family has faced any jail time and it appears unlikely they will.

That’s not to say there are no heroes to be found in the midst of this tragedy. The documentary showcases writers, doctors, and DEA agents determinedly striving to bring the crisis to light. What’s most rage-inducing is how many of their efforts were shot down by politicians in thrall to big pharma’s money. Dr. Art Van Zee, a soft-spoken family doctor from Virginia who was one of the first to track the devastating effects of opioids on his community, brought his concerns before Congress, only to have them shot down by a patronizing Sen. Chris Dodd of Connecticut, where Purdue was based. Art Rannazzisi, a former DEA enforcer who was trying to stop the flow of opioids by targeting major distribution companies like Cardinal Health and McKesson, testified that the deceptively named “Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Art” would handicap those efforts, only to have his expert claims contemptuously dismissed by Rep. Marsha Blackburn and Tom Marino, co-sponsors of the bill, both of whom received hefty payouts from the pharmaceutical industry that actually wrote it. The fact that the bill was passed by unanimous consent of Congress is shameful. One Washington Post journalist who extensively researched the bill said of it, “I don’t think they even read it.”

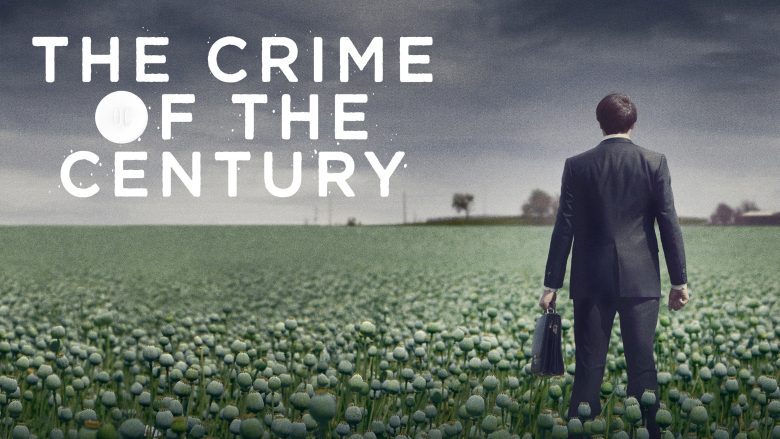

Gibney does an excellent job of making the often-unwieldly information not only informative but accessible. The subject matter is far too grim to be called “entertaining” but his slick production values and reenactments of various crimes combine to keep the interest of even those watchers with short attention spans. At times his way of cutting away from one featured subject to another can be distracting, but overall his choice of interviewees, which include investigative journalists, conscience-ridden salespeople, former addicts and grieving family members results in moments that are powerful and poignant. His habit of interweaving scenes with repeated, panoramic shots of graveyards and poppy fields becomes beautifully ominous.

The Crime of the Century ends with a clip of Rannazzisi, still trying to fight the opioid crisis but now on a grass-roots level after career-destroying fallout from his Congressional testimony. He concludes a speech by playing a recording of a harrowing 911 call from a mother whose son has fatally overdosed, a heartbreaking plea for help that no one, still, seems to be able to answer. Recently the CDC calculated that 107,000 Americans died of overdoses in 2021, and the 2022 death toll is estimated to be even higher. The mother’s anguished cries will haunt you like the documentary it closes does.

– Maureen McCabe.