by Eric Lindbom

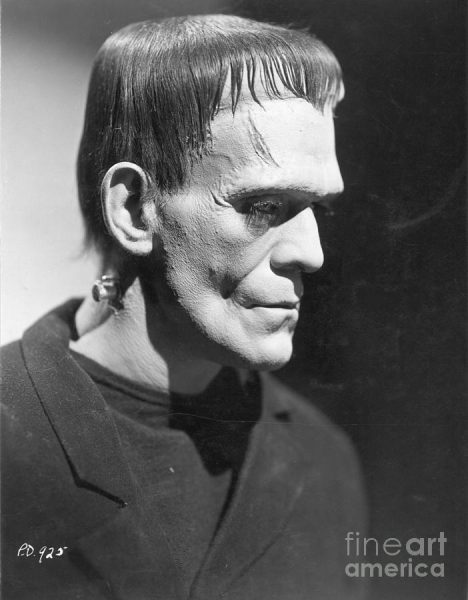

The flat top head with two vertical clamps dripping like metallic sweat over the eyebrows. One shiny bolt protruding from each side of the neck. Stitches on green colored wrists. In your mind’s eye you instantly see an image of the Frankenstein monster.

Our mental snapshot (culled from movies, toys, and models) comes courtesy of Jack Pierce make up master at Universal Studios who also created the signature looks for the Mummy and the Wolf Man.

The Monster was the earliest ghoul I recall from childhood. Mom refused to let me watch old horror movies on TV. So, my six-year-old self eagerly ran errands to a Minneapolis bakery so I could pass a hardware store and gaze longingly at the box cover of Aurora monster models in the store window. The Monster loomed largest.

Scientist Victor, who blasphemously aped God by creating life, was the title character of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. That’s often forgotten today since many casually bestow his Monster with its father’s name (either by mistake or shorthand as Universal eventually did).

The studio served up a classic 1930s trilogy that famously starred struggling middle-aged character actor Boris Karloff. He had mostly played thug roles when director James Whale noted the former William Henry Pratt’s elongated face in the studio commissary. Whale and young producer Carl Laemlle Jr. (who spearheaded the project) eventually chose him for the Monster role over Dracula star Bela Lugosi (their back-and-forth decision on the casting is trenchantly told in Julian David Stone’s fascinating cine-historical novel It’s Alive).

In Frankenstein, Karloff’s equally fearful and poignant performance as the Monster, a confused outcast thrown into an uncaring world, steals the show from a game cast including Colin Clive’s messianic, mad doctor. While creaky in spots, this 1931 early talky still plays thanks to Whale’s ingenious scares big (a fiery windmill climax) and small (the first time we see the Monster, it enters back towards the camera building our dread before it turns and the camera zooms in for a facial close up). A then daring decision to show the Monster accidentally drowning a child so terrified audiences the full scene didn’t re-appear until 1987.

In its day, the film proved a seismic sensation that no horror film rivaled until The Exorcist. Modern audiences invariably prefer the visually brilliant sequel Bride of Frankenstein which hasn’t dated one iota. Whale’s crowning directorial achievement even edges out his terrific take on H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. It features mordant humor that still tickles audiences (especially Ernest Thesiger’s fruity co mad-doctor), a mesmerizing Franz Waxman score and the Bride’s lightning bolt hair do which remains a fashionista fave choice each Halloween. The sequence where a blind man teaches the Monster to haltingly speak still wrings well-earned tears. However, Karloff felt robbing his character of its inarticulate struggles was a mistake.

1939’s Son of Frankenstein, a glossy production from director Rowland V. Lee with eerie, Expressionistic sets, is sometimes dubbed the straight version of Young Frankenstein since many of its characters and sequences were lovingly parodied by Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder. While a now non-verbal Karloff brings his usual menacing and soulful shadings, he cedes screen time to a trio of bravura performances: Bela Lugosi’s conniving hunchback Ygor, Lionel Atwill’s Inspector Krogh (who loses two arms to the Monster – one real and one artificial) and Basil Rathbone’s manic theatrics in the title role. For all its ample virtues, Son showed Karloff the Uncanny (now a brand name) that the Monster was turning into a supporting player so he bowed out of future turns.

While most fans deem Karloff the definitive Monster, pop culture perversely associates the character with the brutish approach displayed by subsequent players. While a burly figure, Lon Chaney Jr. brought no juice in Ghost of Frankenstein inexplicably not taping into his own gift for generating audience empathy. A brisk matinee movie undone by Cedric Hardwicke’s sleepy, bored performance as another scion of Frankenstein, Ghost ends with the Monster turning blind after a brain transplant with Lugosi’s Ygor.

That narrative thread was jettisoned in the friskier, far more atmospheric Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man. Lugosi portrays the Monster, a role he once decried, and spends much of the film flailing around sightless with no explanation for bewildered audiences. His spastic pantomimes turned into a regular trope of Monster imitators decades later. At least Lugosi’s Monster makes frequent appearances in a chilling work ably directed by Roy William Neill but dominated by Chaney Jr’s trenchant second turn as werewolf Larry Talbot.

Most fans, including yours truly, feel the second finest Universal Monster was Glenn Strange a physically imposing character actor (later a regular on Gunsmoke). He played the Monster as a slow moving savage but his nightmarish take has real bite.

Sadly, in two consecutive “monster mash” team ups, House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula, Strange is third banana behind Chaney Jr’s Wolf Man and John Carradine’s courtly, convincing Dracula. In both, the Monster takes on prop status, splayed on a lab slab before briefly rising to life, throwing a hunchback through a window and then croaking on cue.

While churlish fans might view the concept of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein as heresy, this greatest of horror comedies brought more legit scares than either House entries (as well as Lugosi’s too-long delayed turn as Dracula and Chaney Jr. donning the fur in a mask since Jack Pierce was unceremoniously retired earlier). Best of all, Strange finally gets ample screen time terrifying Lou Costello whose squeals of fright are contagious. Anyone casting a gimlet eye needs to see A&C Meet F with a laughing, shuddering audience.

Because Universal closely guarded the rights to the Monster make up and appearance, Britain’s Hammer studios devised a shrewd workaround. The studio created an estimable Technicolor cycle focusing not on the Monster but Baron Frankenstein (vividly realized by Peter Cushing as a haughty scientist who grows more evil with each installment). In Curse of Frankenstein, Christopher Lee is cast as the Creature (the lawyer-approved new name) but the makeup makes him resemble a third-degree burn victim. The subsequent Hammer Frankenstein cycle (Revenge of Frankenstein, Evil of Frankenstein, Frankenstein Created Woman, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed and Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell) is generally smart and at times provocative with sporadic shocks and graced by high production values. The connective tissue is Cushing’s tragic arc from egotistical brilliance to insanity.

More recent attempts at exhuming Frankenstein are high-minded though not necessarily effective. Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein suffers from vertigo-inducing, hyperactive camera work and a miscast Robert De Niro as the Monster. The British television mini-series Frankenstein: The True Story hews much closer to the source material with sensitive Creature work from Michael Sarrazin. With a starry cast (James Mason, David McCallum, Jane Seymour, Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud, Agnes Moorhead) and a script from Christopher (The Berlin Stories) Isherwood, it’s an intelligent, ambitious production but more for the Masterpiece Theater crowd than we humble gore hounds. Presently, Guillermo del Toro is prepping his own dream project version.

There’s also been a crypt full of intended or unintended kitsch flicks playing off the title over the decades (Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein, Frankenhooker, Frankenstein Island, Frankenstein Conquers the World, Frankenstein 1970, Blackenstein and kid-friendly riffs like Tim Burton’s Frankenweenie and TV’s The Munsters which Rob Zombie is reportedly cine-adapting).

However, let’s get real. When I think of Frankenstein’s Monster only the Glenn Strange adjacent Aurora model box cover will do.

Eric Lindbom is a hardcore horror buff with a strong stomach, weaned on the Universal classics from the ’30s and ’40s. He’s written film and/or music reviews for City Pages, Twin Cities Reader, LA WEEKLY, Request magazine and Netflix. He co-edits triggerwarningshortfiction.com, a site specializing in horror, fantasy and crime short stories with illustrations by co-editor John Skewes. He lives in Los Angeles.